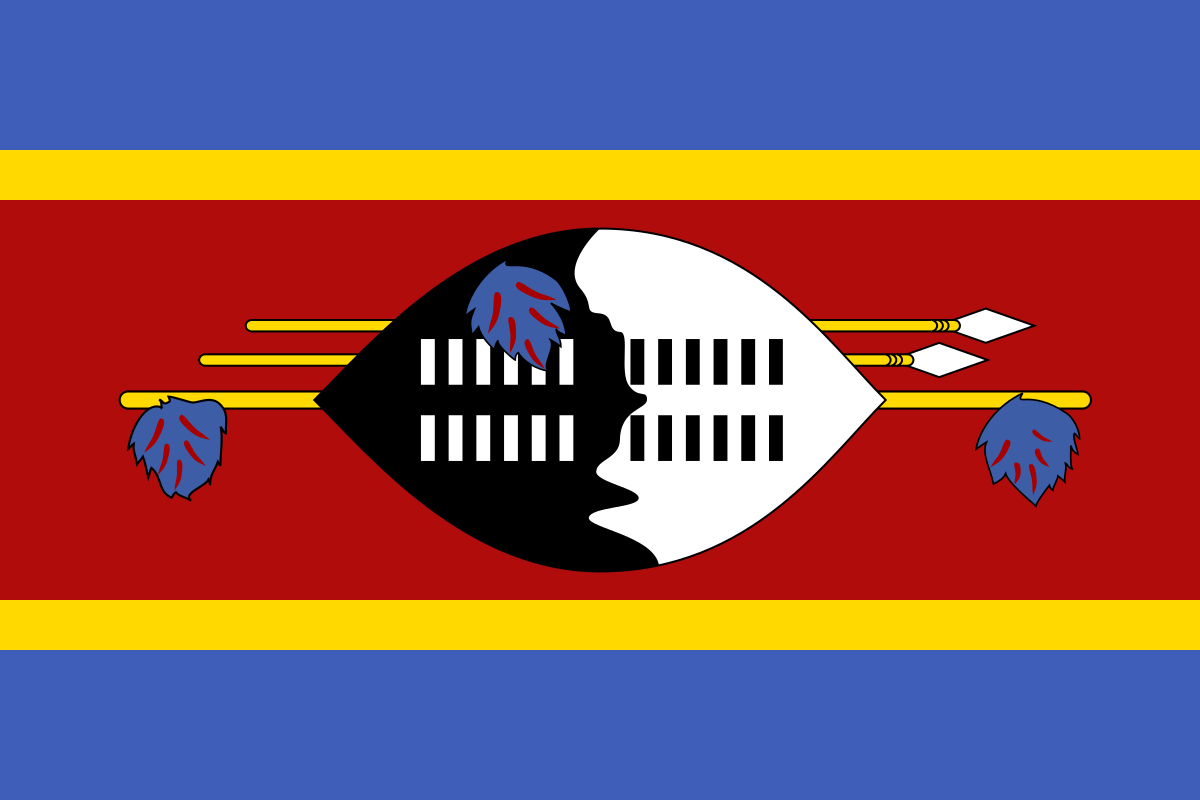

Judicial independence at stake in Swazi name-change suit

25 Jul 2018

When Swaziland’s King Mswati III declared the name of his country changed, forthwith, to Eswatini, it was met with scepticism from many commentators who said the desperately poor country should not be spending time and money on such issues. Not three months later, the issue is being challenged on legal grounds: a human rights organisation has launched an application testing the constitutional right of the king, ‘Africa’s last absolute monarch’ to make unilateral changes to the country’s name. Carmel Rickard, in her A Matter of Justice column on the Legalbrief website, sees this as a major test of the independence of the judiciary in that country, whose judges were instructed by a previous chief justice not to hear any case that challenges or criticises the king.

————————————

Less than three months after King Mswati III’s declaration that his country’s name had changed comes a direct challenge to the legality of that decision. Brought by the Institute for Democracy and Leadership (Ideal) and its director, prominent Swazi human rights attorney and ‘citizen of Swaziland’, Thulani Maseko, the court application goes directly to the power of the king and also of the Chief Justice who has already ordered that court documents now reflect the name ‘Eswatini’.

The non-profit organisation of which Maseko is a director aims to protect ‘the rule of law, democracy, good governance, human rights and social justice for all’. It is also dedicated to monitoring the conduct of organs of state to ensure power is exercised in accordance with the constitution and that ‘judicial independence and accountability’ is maintained.

In his founding affidavit, Maseko says that the constitution of Swaziland, which is the country’s supreme law, gives every person the right and capacity to enforce the bill of rights and to promote and defend the rule of law.

It also defines Swaziland as a democratic country whose citizens have a stake in the ‘decision-making process pertaining to the change of name of the country’.

It was essential that the government of Swaziland and all its officials exercised power within the parameters of the supreme law and the constitution itself spoke of the ‘right and duty’ of the King and all citizens to ‘uphold and defend’ the constitution.

In issuing a legal notice of the name change, the King assumed power he did not have, Ideal says. ‘His Majesty is not endowed with delegated legislative powers in this instance.’

The right of citizens to be involved in such a decision also contravened international human rights law, for example the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Swaziland, which specifies that ‘every citizen’ has the right to take part in public affairs, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights which has a similar provision.

Through the application, Ideal wants to enforce the right of all citizens ‘to participate in the decision to change the name of the country’.

The case was brought against the Government of Swaziland because ‘it is not authorised to act in terms of any law or legal document that is ultra vires’, and against the attorney general in his capacity as the legal advisor to the government and to the King.

The matter ‘goes to the heart of the rule of law’ in Swaziland. The court had the authority to ‘hear and determine any matter of a constitutional nature’ and since the case raised the fundamental question of the exercise of power by the King, it was a matter ‘of a constitutional nature’.

Maseko’s central contention is that the country’s name could only be lawfully changed via a ‘legislative process, including citizens’ participation and public involvement’. Instead, however, the change was simply ‘announced’ by the King at a celebration to mark his 50th birthday. Several government departments have already changed their names accordingly. For example, the Chief Justice has ordered that all court documents will now carry the name ‘Eswatini’ rather than ‘Swaziland’.

‘As a citizen and a lawyer (Maseko) is aggrieved that the name of the High Court of Swaziland … is being changed by simple notice.’ Similarly, the name of the Supreme Court of Swaziland, entrenched as such in the constitution, ‘has now been changed to the “Supreme Court of Eswatini”.’

These and other changes were made without any legislative process ‘or any lawful process at all’, even though the Chief Justice has no legislative powers. The constitution made clear that the powers and functions of the chief justice ‘do not include the power or authority to change the names of the courts, which are provided for by statute and the constitution’.

The King did not have the constitutional power to declare a change to the name of the country; that necessarily involved a change to the constitution and the King did not have the power to make such an amendment.

Such a change required citizen participation, something guaranteed in the constitution.

Maseko makes another point about the name change: Eswatini does not seem in any case to be the country’s original name. That is ‘kaNgwane’, he says, adding that this appears clear from the ‘SiSwati version of the constitution’.

The executive prerogatives of the King were not unlimited and there was no provision that the King could make constitutional changes ‘by declaration’. Fundamental changes to the constitution, such as the renaming of the country, requires a complex and specially delineated process.

He says the people ‘have been denied the right to be involved in the critical decision in changing the name of our country. The decision is clearly unlawful and unconstitutional’.

The King is bound by the constitution and if the name change is allowed to stand, the principle of legality will be undermined.

The application also canvasses the financial implications of the name change, pointing out that the people have not been informed of the cost implications, particularly at a time when the government was struggling to meet its obligations such as paying its wage bill.

Human rights organisations around the world will closely watch the development of this case, and not just because of the issues raised on the papers. It could also prove a moment of truth for the country’s judiciary: in 2011 the then-Chief Justice, Michael Ramodibedi, issued a directive that effectively barred all the country’s courts from considering legal claims against the King or his office and the CJ suspended a judge who, according to him, had done just that.

This was followed, in 2014, by an infamous decision, Law Society of Swaziland v Simelane, which stated that the king was exempted from any legal action ‘flowing from all things done by him’. The court added, ‘Under no circumstances therefore should any litigant attempt, directly or indirectly, to challenge the authority of His Majesty the King in any cause in respect of all things done or omitted to be done by him! Once the King has spoken it is the end of the matter. It is final.’

Given this background, the application by Ideal and Maseko is a full-frontal test of the courts’ willingness to show independence and impartiality when it comes to matters involving the King and the way he uses his powers. And it is brought by a human rights lawyer who is no stranger to the inside of Swazi jails: Maseko, along with journalist Bheki Makhubu, spent time behind bars on the orders of Ramodibedi, in punishment for what the then-Chief Justice decided was contempt of court related to their criticism of the judiciary for its lack of independence. Ramodibedi has since left office in disgrace.

See also: Iceland and the pitfalls of geographic names

(This article is provided for informational purposes only and not for the purpose of providing legal advice. For more information on the topic, please contact the author/s or the relevant provider.)